Something came on my path at work in the past weeks that I am super stoked about! So I couldn’t resist to write something about a very cool bit of maths/geometry with a some company history, a surprising application and even some arts & crafts thrown in!

Some LIME history

A company that manufactures packaging machines for the food processing industry traced us - Sioux Mathware - down as the descendants of the original creators of a small script that they use to create “forming shoulders”. This script was created somewhere in the early 90’s and could use some modernization, which is why they reached out. So as I write, we are formulating a proposal for a project. Not knowing whether it will land, I can’t contain myself to already write some of the history and maths (which is public) down. No code this time though.

My working career started in August 2012 with LIME B.V.. LIME was an acronym for ‘Laboratory for Industrial Mathematics Eindhoven’. LIME was created somewhere around 2005 at the Technical University of Eindhoven (TU/e) by Prof. Bob Mattheij. Just before I joined, 2011 or early 2012, LIME spun out of the university and was acquired by Sioux, which was mostly a software company back then. Some milestones in the history of LIME since 2012 were

- The branding of the company through “slimoentjes” around 2018 (with the main header to this blog being The March of Progress reinterpreted with “slimoentjes”)

- Becoming the Mathware department of Sioux Technologies in 2020. Over the span of my employment, Sioux as a whole has evolved from a software company into a “systems house” that houses nearly all of the engineering disciplines.

The history before 2012, I knew mostly through word of mouth by colleagues who’ve been here longer than me. So I knew that LIME originated around 2005. But a screenshot of the forming shoulder script stated “Instituut Wiskundige Dienstverlening Eindhoven” (IWDE, Institute of Mathematical Service Eindhoven), so I went digging at little bit. Helpful at that is how the Eindhoven university publishes many university documents on their website. In my daily work I regularly consult master theses and PhD theses, which afaik the KULeuven still does not publish online. TUDelft and other Dutch universities as well, so perhaps its a Dutch thing… Anyways, this time around, I used the repository for more historical documents. One document that can be found there that gives a view into LIME history is the Liber Amicorum of Bob’s retirement from the university. Bob retired in 2011 and stuck around at LIME until 2018 (at which point we made him another Liber Amicorum or “book of friends”). That TU/e document is a testament to Bob’s lifelong engagement to close the gap between mathematics and industry, through a plethora of initiatives, like ECMI, SIAM, ITW, SWI, and eventually LIME. However, it does not state anything about the IWDE…

Another piece of the puzzle though, was that we quickly found some literature on the mathematics of forming shoulders, the oldest one being this 1989 paper by Jaap Molenaar with nice old mathematical type setting titled “Shoulder design for packaging machines”. Jaap Molenaar was familiar to me as a old co-worker of Bob, as we participated in the same team at the SWI 2019 where we jointly pondered a week about modelling the stability of concrete 3D printing (a challenge submitted by Bruil). At the time of writing, Jaap is professor emeritus from Wageningen University (WUR), but at the 2019 SWI he was still active as professor there. Before his professorship in Wageningen however, he worked for many years at the IWDE. Once again, the TU/e document repository proved a very interesting resource containing year reports of the IWDE. The earliest one I could find was the 1988 IWDE “jaarverslag”, the latest one being the 2001 IWDE “jaarverslag”. Both were published by Jaap Molenaar and give some insight into the IWDE. I am very impressed by the amount of activities, projects, publications, conference presentations, courses, … by the IWDE group in those reports, given that they were <5 full time people.

And yes, the 1988 report makes mention of the Aquarius company (their name back then), looking for help with the mathematics of their forming shoulders… With a history of over 35 years, this makes it by far the oldest LIME activity that I’m so closely involved with. Anyways, enough with the history: What are forming shoulders anyways?!

Forming shoulders

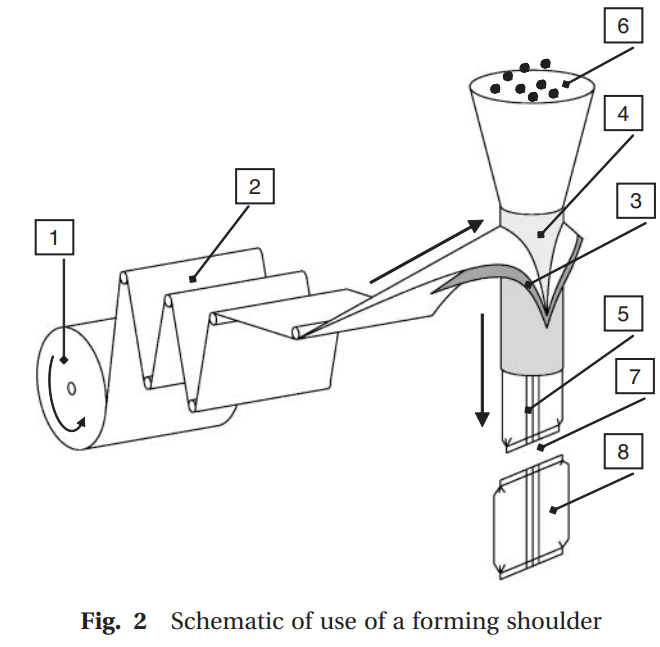

As a picture says more than a thousand words, check out the image below.

This depicts a roll of plastic [1] being shaped into a tubular shape, that tube being sealed [5], filled (think of m&m’s) [6] and sealed and cut into individual bags [7,8]. The forming shoulder is [3], a component that guides/shapes the plastic into a tube. Below a picture of a true forming shoulder:

The function of this shoulder is to shape the plastic without stretching, tearing, wrinkling, … In order to achieve that, some very interesting mathematics is used, namely the mathematics of developable surfaces. Developable surfaces are those surfaces that can be deformed into flat planes without tears or wrinkles. This means local geometry is preserved, such as distances and angles. Mathematical theory states that such surfaces need to have Gaussian curvature zero everywhere. They can be curved, but they always need to be straight along some direction. “Doubly curved” surfaces (like spheres) are not developable. That is why there is an entire science about map projections for Earth, as there is no perfect solution. Another typical application is in how holding a piece of floppy pizza and intensionally folding is along the axial direction avoids it from sagging along the longitudinal direction.

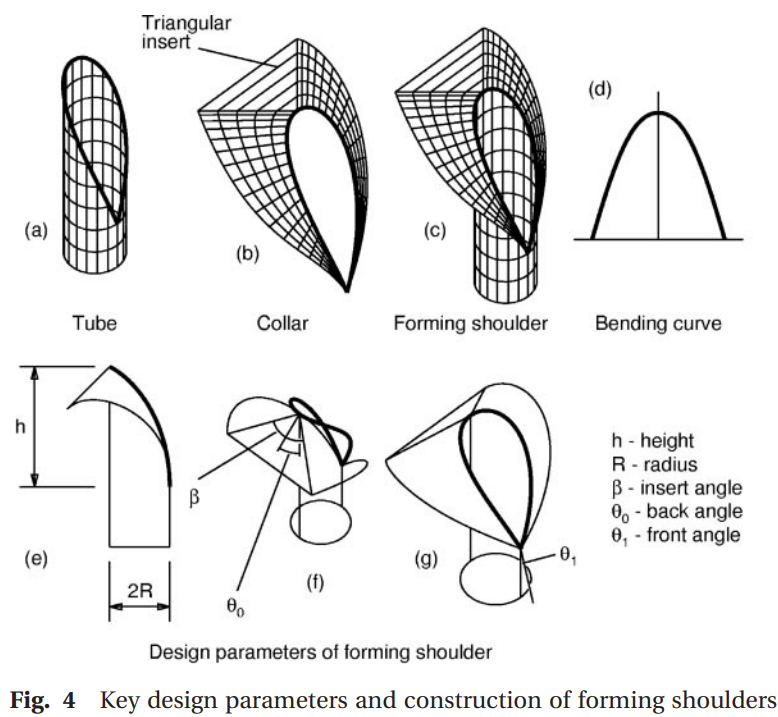

Developable surfaces are ruled surfaces (but not necessarily the other way around), which means that on every point, there is a straight line that is completely contained on the surface. A forming shoulder is not a single developable surface, but a union of two developable surfaces that meet at a bending curve. The constraint that one of the two developable surfaces is a (part) of a cylinder, imposes constraints on what the other developable surface (the collar) can be.

Jaap Molenaar, during his time at the IWDE, was the first to derive and publish the theory and solution of what this bending curve and collar shape are. He did so in a 1989 IWDE report, but later also wrote a extended, peer reviewed version with nicer typesetting in this 1995 SIAM review paper. Later on, professor Ben Hicks was involved in two publications that cite Molenaar and that have some nice visuals (that I use in this blog post), e.g.:

- Design of forming shoulders with complex cross-sections

- Towards an integrated CADCAM process for the production of forming shoulders with exact geometry

A core part of the solution to the mathematical problem is the bending curve, which, when the tube is unrolled, looks a lot like a parabola. In fact, the formula is

\[f(\xi) = c_0 + c_2 \xi^2 + c_3 |\xi|^3 + c_4(\cos(\xi) - 1 + \xi^2/2) + c_5|\sin(\xi) - \xi - \xi^3/6|\]Which is in fact a parabola with some additional terms on top. We have 5 parameters to the bending curve, that are related to the design parameters like the angle of the incoming film, the radius of the tube, the height between top of the bending curve and bottom of the bending curve, … For the math details, you should check out the papers.

Manufacturing forming shoulders: arts & crafts

In this final section, we discuss 3 possible ways of manufacturing forming shoulders for industrial application, and how 2 of them you can copy in your own home.

The very first way is to create a solid shoulder using additive or subtractive manufacturing like 3D printing or CNC milling. Both of them require the full mathematical toolbox, as the full 3D geometry needs to be described. Moreover, I could not thing of a simple way to replicate that at home.

Molding and the paper towel shoulder

The second way of manufacturing a forming shoulder is the least mathematical way. In fact it avoids it completely by relying on the physics of deformable surfaces. The manufacturing technique I’m talking about is molding, e.g. from clay. You wrap some sheet material around a tube, and fold one end like a collar of a shirt (yes, also that is very much related to the mathematics above). If you do this upside down, you can fill the collar shape with your molding material. The trick is that the sheet material should be not too stiff to be easily foldable, but stiff enough to serve as a mold.

At home, you can replicate this process with paper. However, if you were to use ordinary printing paper, you would experience that it is too stiff and that you need to wrinkle it and you wouldn’t get a nice solution. In my search for some sheet material that is not as stiff a paper, but not as weak as say a towel, if found a perfect balance in… you guessed it… paper towels! The dimensions of our paper towels at home were such that the tube whose circumference matched best was a bottle of wine. Just wrap it around the bottle, tape together the bottom 5-10cm and fold the upper part down. Below, you can behold a very nice example of your own forming shoulder at home, with no mathematics needed at all! And a bonus is that this shoulder is still deformable, so you can vary the parameters mentioned earlier easily.

Sheet bending and the printing paper shoulder

The final way to manufacture a shoulder the most fun one and uses some of the maths, but relies on physics for the rest. We are talking about creating forming shoulders by bending a reasonably stiff plate material, like 1mm stainless steel plating. For this process we need only the mathematics of the bending curve. This curve is to be given to a laser cutter to cut your plate material in two along that parabolic shape. The two parts can be bent into the individual developable surfaces (tube and collar) and joined by welding them together at the (curved) bending curve.

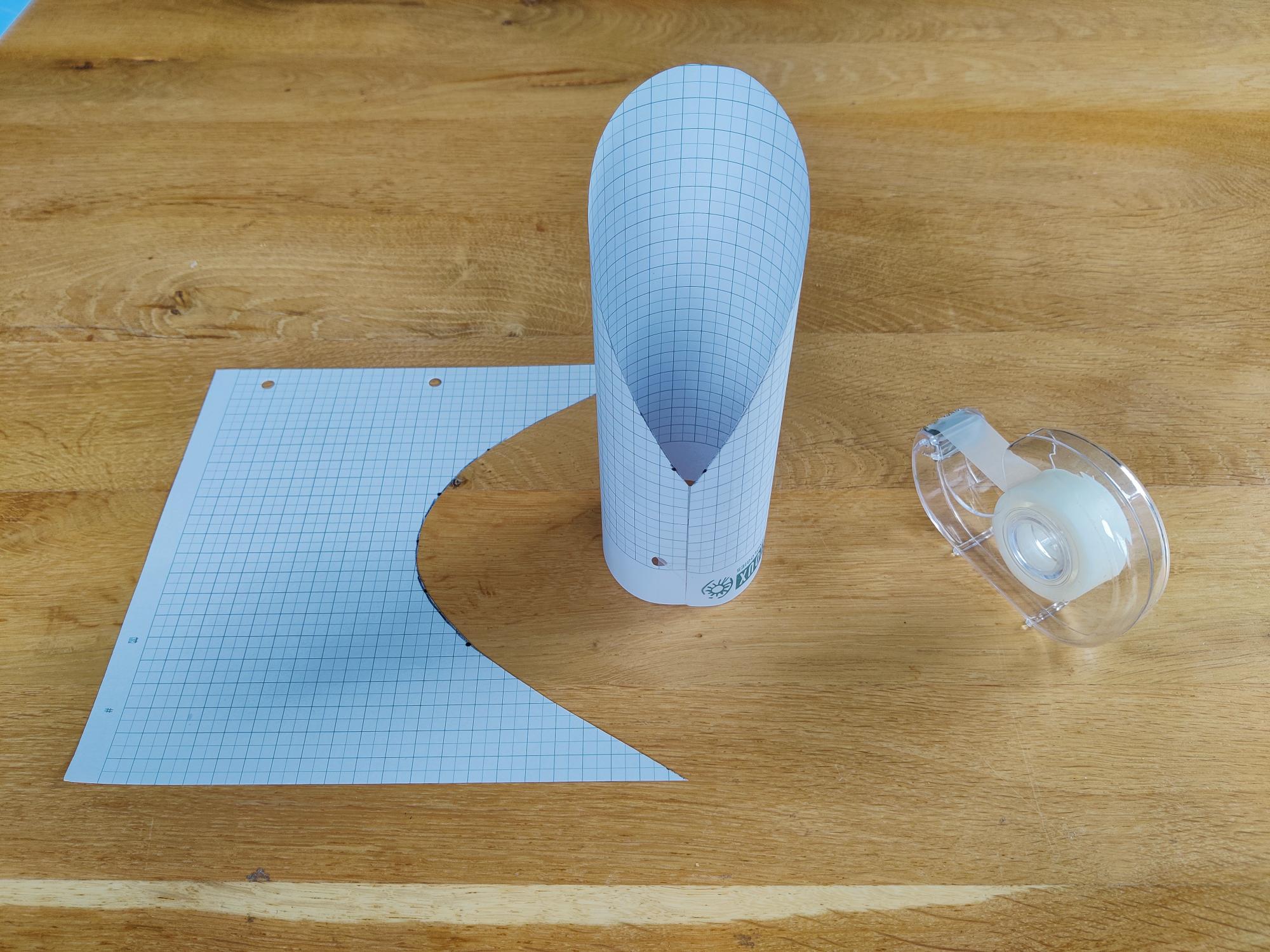

Where our printing paper was too stiff for the folding method, it serves perfectly to illustrate the stainless steel plate example. Step by step:

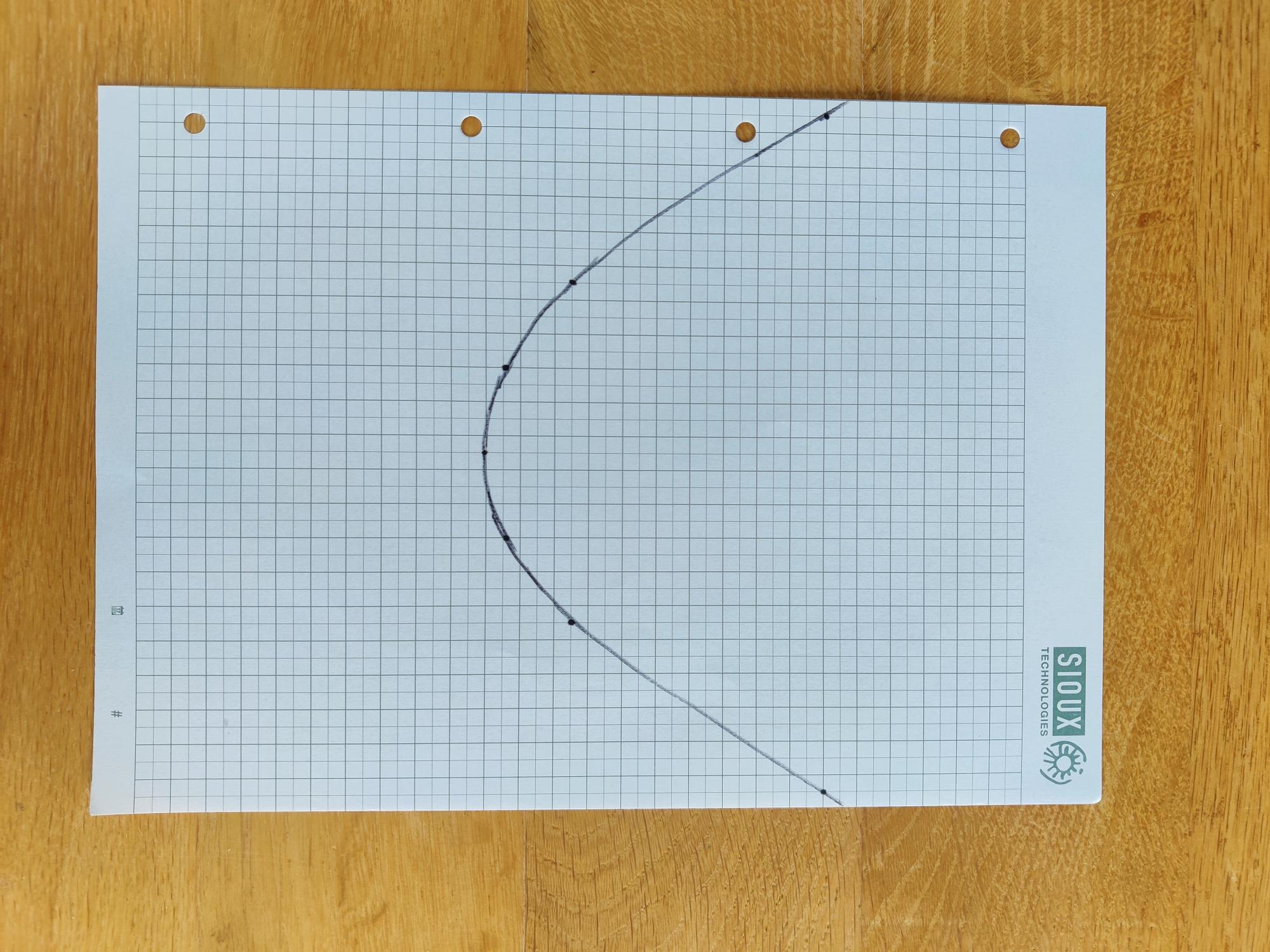

Step 1: Draw the cutting line

See the (sole) equation above, or something simpler like a parabola. For 21cm wide A4 paper, I chose my parabola to be 10cm in height (which was easy to draw on my grid notebook paper). After bending, this will yield an insert angle which is almost a right angle. Put the parabola such that the collar part is not too long, as your final product will not stand upright and tip over.

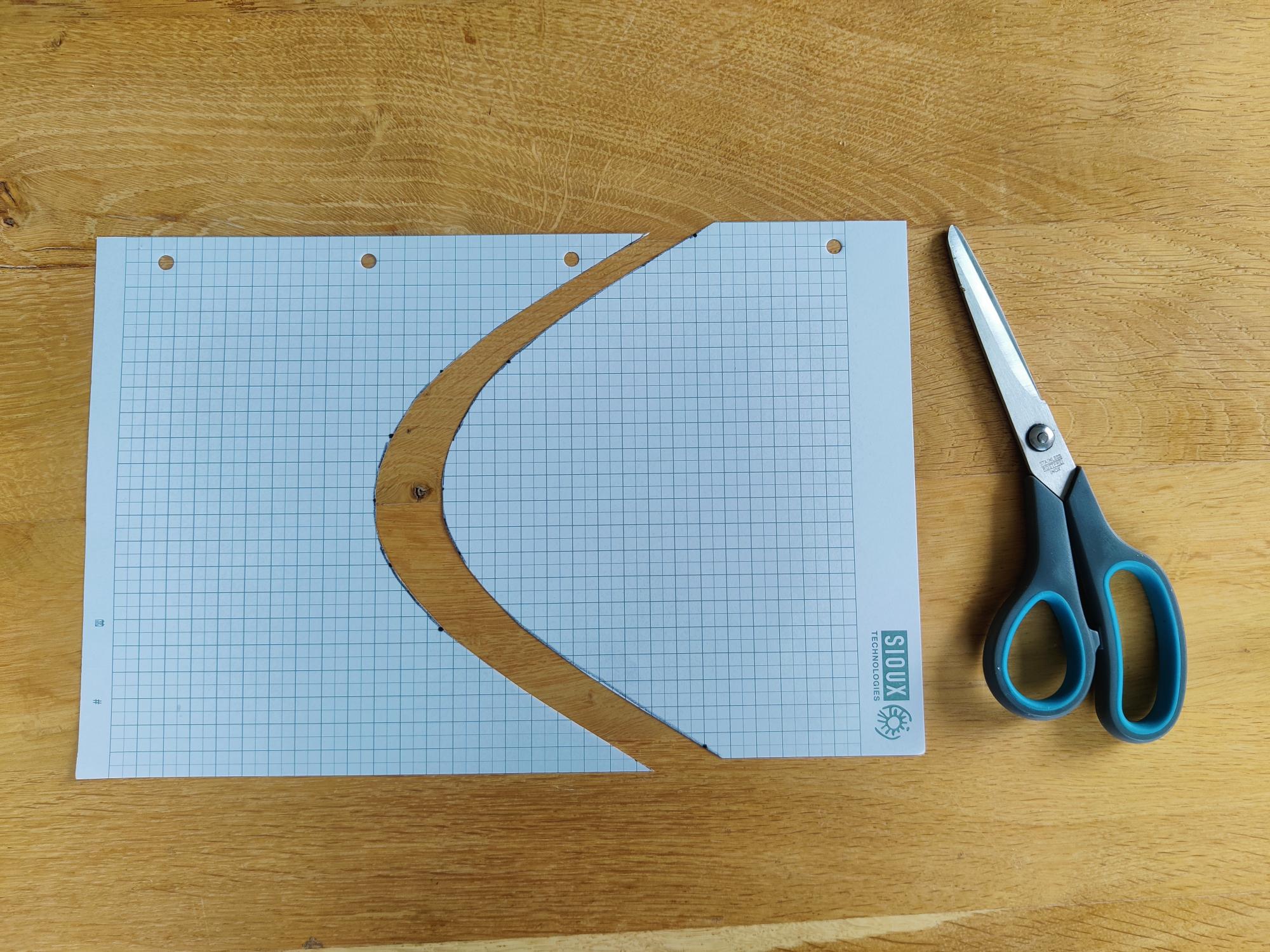

Step 2: Cut the paper

We’ve replaced our laser cutter with ordinary scissors.

Step 3: Tape the tube

After a little bit of tape, the homogeneity of the papers mechanical properties will make for quite a good circular cross section.

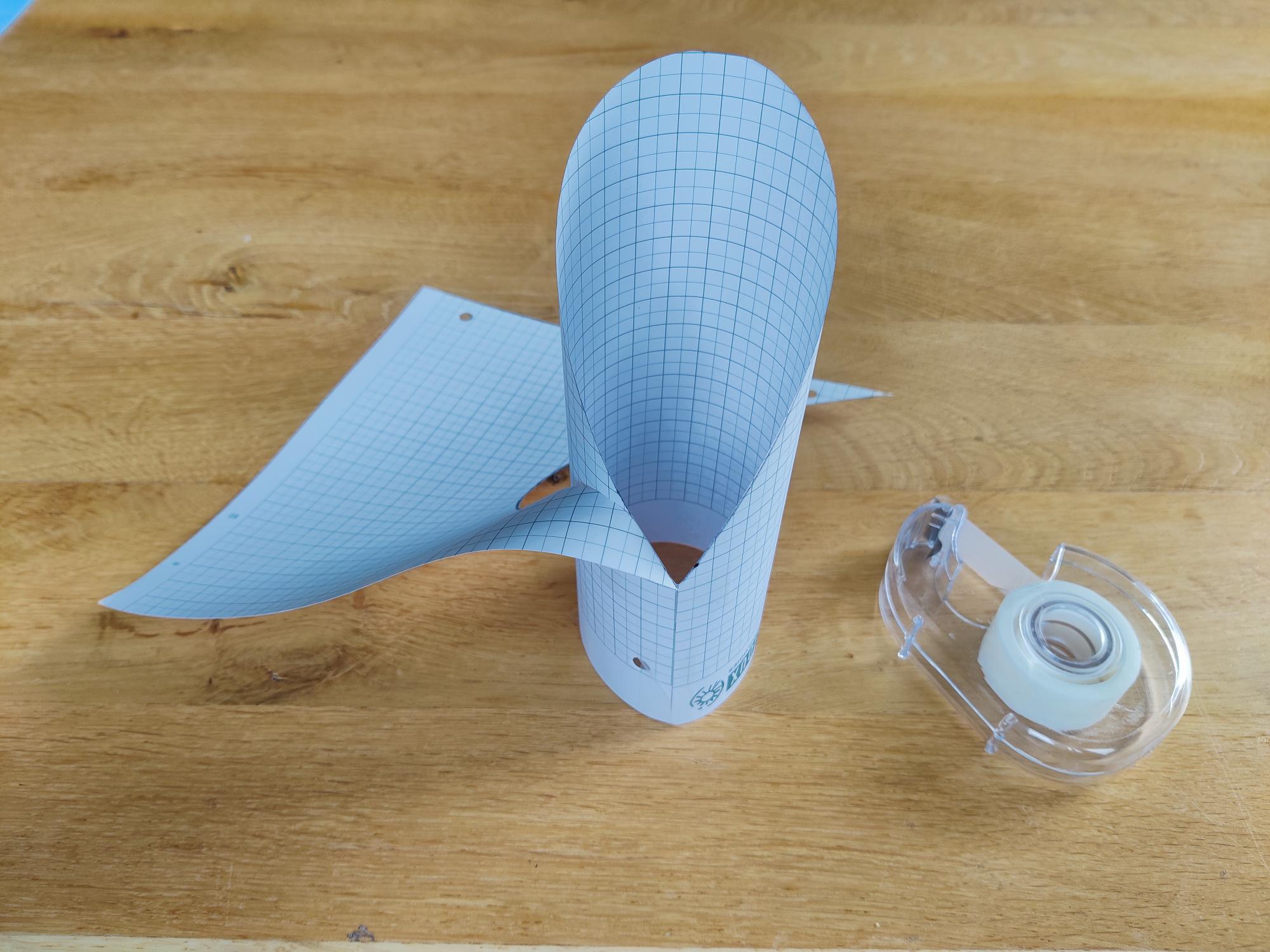

Step 4: Tape one side of the collar

Where we now use tape to join the collar and the tube, with steel one would weld.

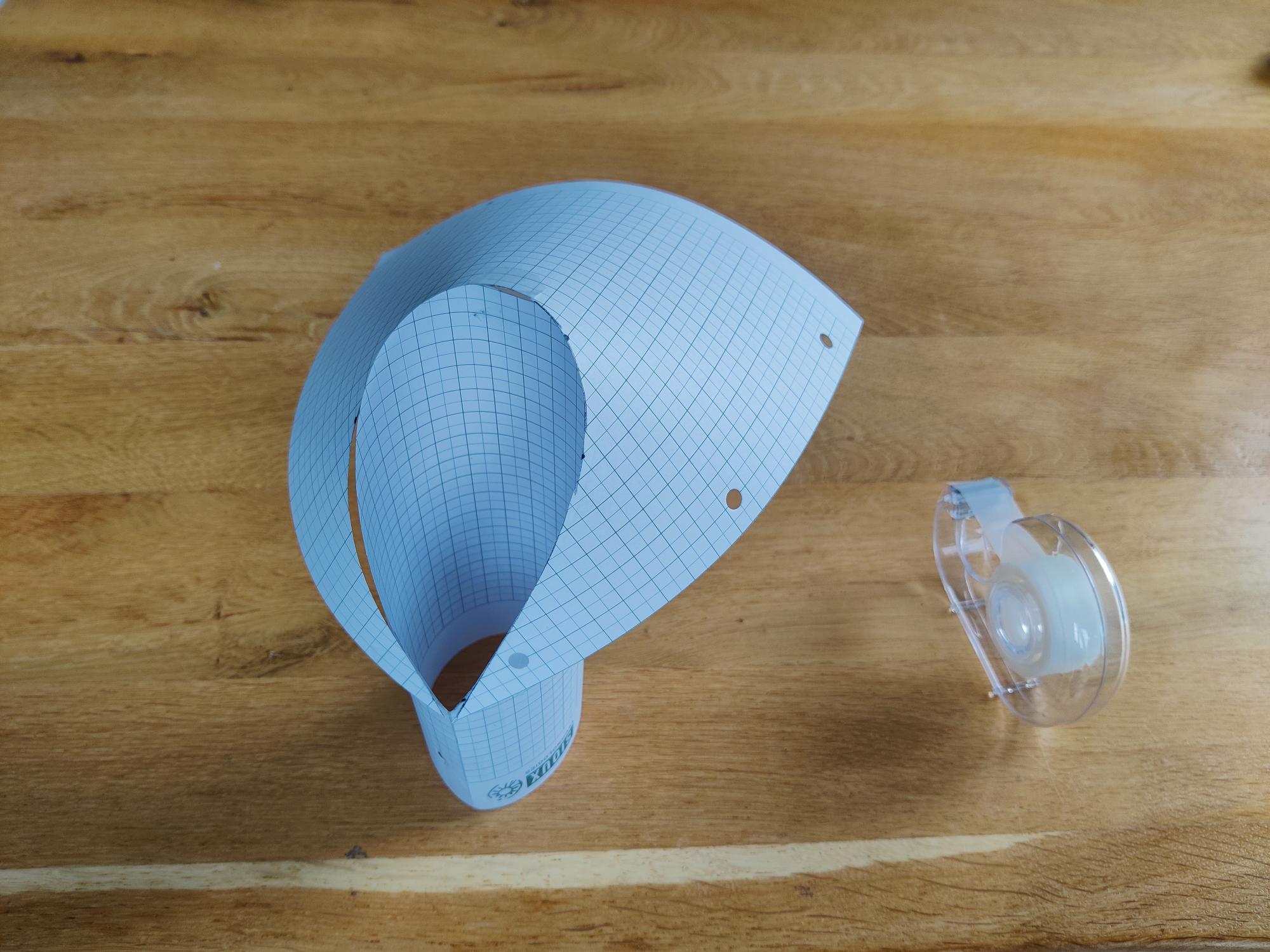

Step 5: Tape the rest, et voila!

Having three connection points (top and the two collar ends) is already enough to get quite a good join across the whole bending curve (as mathematics would dictate).

I imagine this could some fun recreational maths activity to enjoy with kids or students. If anyone would ever do so inspired by this post, be sure to let know!

And I’ll keep you posted whether we landed a 2024 successor project to this ancient little gem.

Related posts

Want to leave a comment?

Very interested in your comments but still figuring out the most suited approach to this. For now, feel free to send me an email.