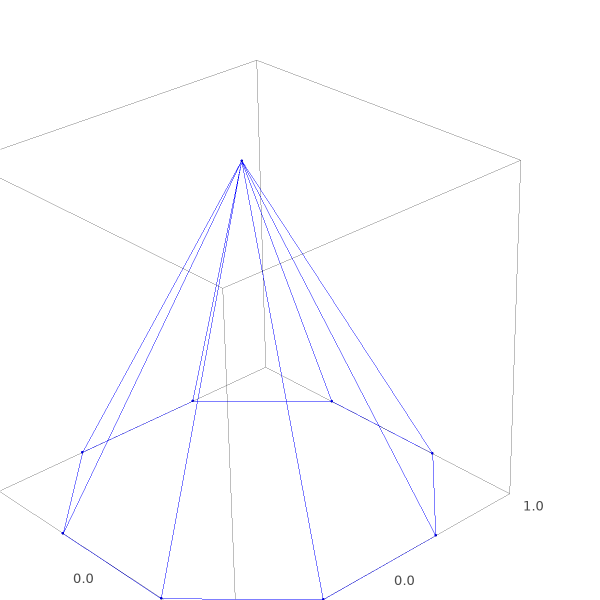

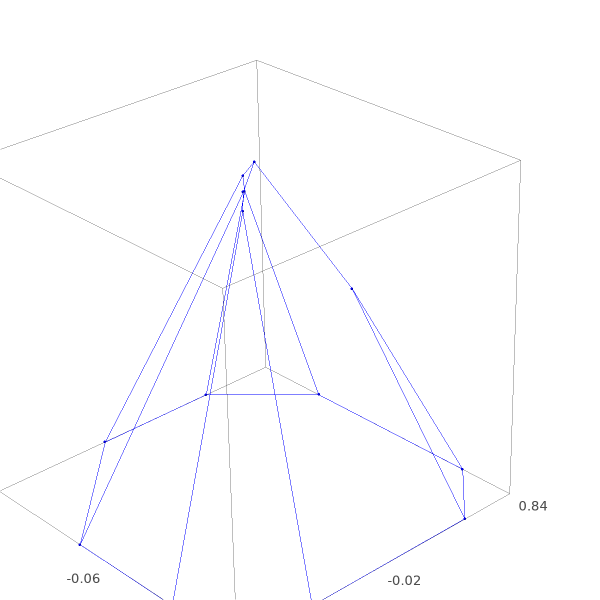

2 years ago, also during the Christmas holidays, I wrote up a blog post about linearly dependent constraints and how they are often discarded in theory, but are quite prevalent in practice. The subtitle was: “Bonus: a nice constraint visualization tool”. Sage was used to generate the figures below

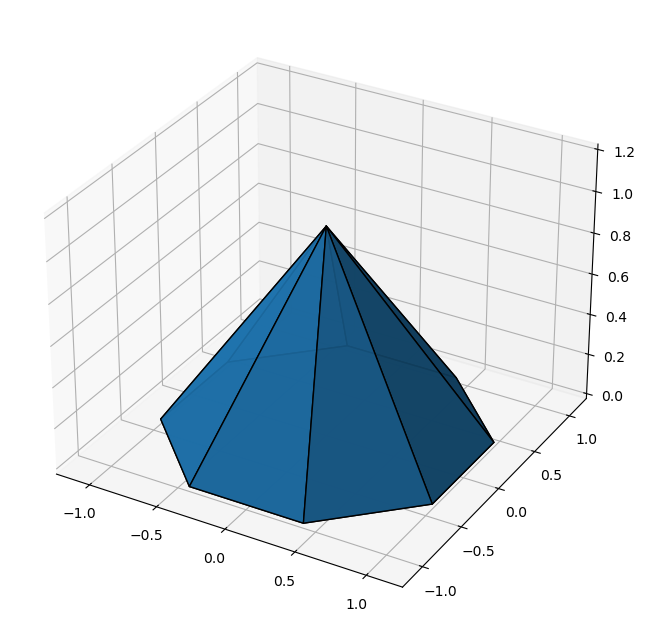

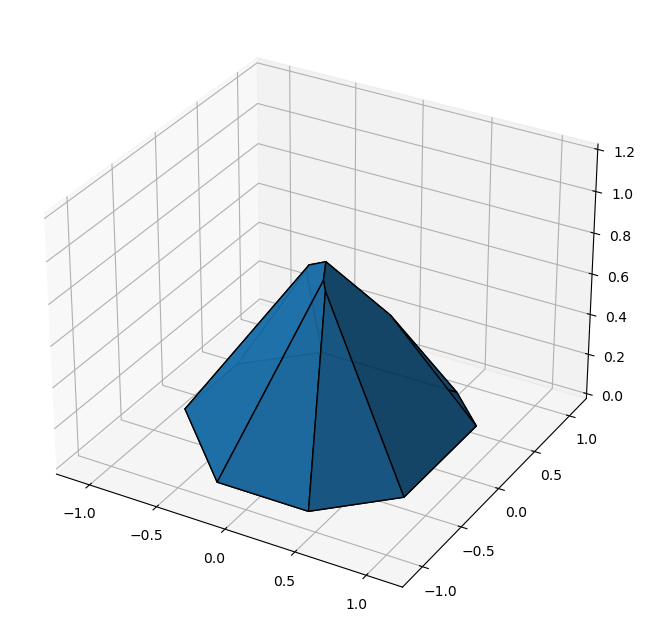

The first one, an octogonal pyramid, has a top vertex which is degenerate from a linear inequality constraint point-of-view. A perturbation to the linear inequality constraints yields the second polyhedron which has no degenerate vertices.

However, that ‘nice constraint visualization tool’ was a bit of a hyperbole. Sage could be used through some web portal, but to run it locally I used a Ubuntu VM. The plotting engine did not give very fancy pictures either. In this blog post, we’ll improve greatly upon that approach with a Matplotlib (and Numpy + SciPy) based visualization!

A little project background

What set this new post in motion, is the discovery (on my part) of the MATLAB con2vert function which was the missing piece of the puzzle. I learned about this function through a new commercial project for a small company from Roosendaal called Kameleon Solar. Kameleon Solar is a company with a very cool proposition: Replacing traditional facade construction materials (like brick) with solar panels. To satisfy aesthetic desires, the solar panels can be any color or even an image, by printing on them. Printing on a solar panels lowers their power yield, and my sound crazy. But Kameleon Solar argues that one should rather compare to the traditional facade materials like brick, which don’t yield any power. You save money by not having to use these materials. And the resulting payback period for the printed solar panels would turn out very well, despite the lower power yield.

One of the mathematical challenges that Kameleon Solar faces is all about color theory and the challenge of printing on a dark background. In color theory, one encounters convex combinations of pure colors / ink channels, which is how I came in contact with con2vert and vert2con: MATLAB routines to convert between two representations of convex polyhedra: constraints (read: linear inequality constraint) and vertices (and closely related, a mesh with vertices, edges and faces).

But before we dive into those, the first minimal requirement for visualizing constraints with matplotlib is to check out its mesh/polygon visualization capabilities

%matplotlib inline

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from mpl_toolkits.mplot3d.art3d import Poly3DCollection

import scipy.spatial

Plotting 3D polygons with matplotlib

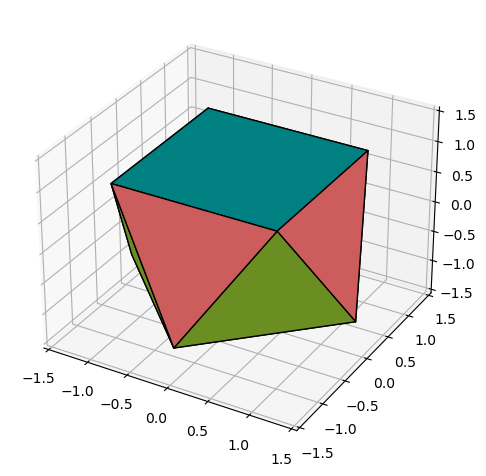

We start out with some code snippet from a great Stackoverflow answer:

z = 2**(1/2)

v = [ [1,1, 1], [-1,1, 1], [-1,-1, 1], [1,-1, 1],

[z,0,-1], [ 0,z,-1], [-z, 0,-1], [0,-z,-1] ] # 8 vertices

f4 = [ [0,1,2,3], [7,6,5,4] ]

fa = [ [0,3,4], [1,0,5], [2,1,6], [3,2,7] ]

fb = [ [4,5,0], [5,6,1], [6,7,2], [7,4,3] ]

f = f4 + fa + fb # 10 faces

verts = [ [ v[i] for i in p] for p in f] # list comprehension

colors = ['teal']*2 + ['indianred']*4 + ['olivedrab']*4 # 10 colors

fig = plt.figure(figsize=plt.figaspect(1))

ax = plt.axes(projection='3d')

ax.set(xlim=(-1.5,1.5), ylim=(-1.5,1.5), zlim=(-1.5,1.5))

ax.add_collection3d(Poly3DCollection(verts,facecolors=colors, edgecolor='k'))

fig.tight_layout()

plt.show()

Hooray, we can plot polygons in 3D. The Poly3DCollection takes a list of polygons for input. Each ‘polygon’ in that case is a $N \times 3$ array (or similar is list format) with the $N$ vertices of the polygon. The post also nicely devulges into what happens if $N > 3$ vertices are not coplanar, which yields rendering artifacts. Additional arguments to the Poly3DCollection are lists of face and edge colors, and also a shade boolean argument that we’ll play around with later.

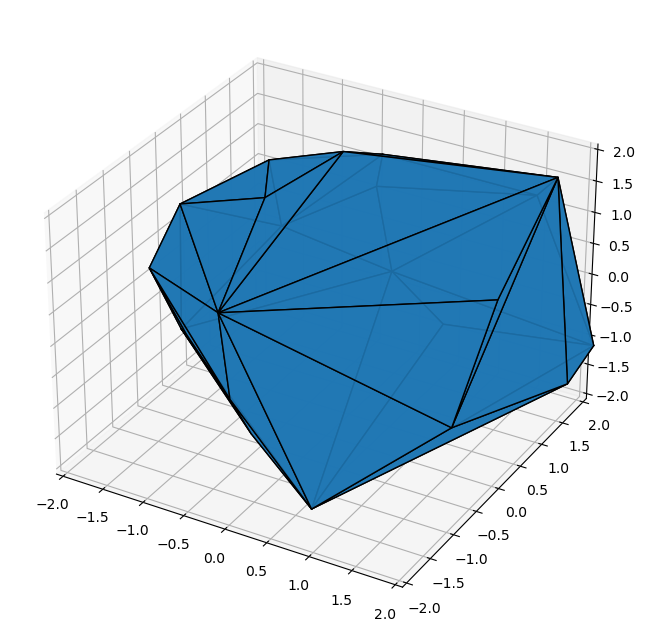

Plotting convex hulls

Before expanding on the con2vert function, one could infer that this returns vertices, rather than polygons. However, as we will be dealing with convex polygons (as only those correspond to linear inequality constraints), lets visualize a convex hull of some random points.

np.random.seed(0)

xyz = np.random.randn(100, 3)

hull = scipy.spatial.ConvexHull(xyz)

print(type(hull))

<class 'scipy.spatial._qhull.ConvexHull'>

print(list(hull.__dict__.keys()))

['_qhull', 'simplices', 'neighbors', 'equations', 'coplanar', 'good', 'volume', 'area', '_vertices', 'nsimplex', '_points', 'ndim', 'npoints', 'min_bound', 'max_bound']

scipy.spatial.ConvexHull is a wrapper to the ubiquitous Qhull library. A key attribute of the output datastructure for our visualization purposes will be the simplices attribute. This is also the main output of the MATLAB

hull.simplices.shape

(40, 3)

The convex hull of our 100 random points has 40 simplices that bound the polygon. The simplices attribute is a $40 \times 3$ array of indices that references the first dimension of the input point cloud xyz, which is also stored in the ConvexHull datastructure points attribute. 2D simplices, which are nothing more than triangles, reference 3 corner points, hence the width or 3 (not to be confused the width of 3 of the points attribute…).

This list of simplex corner indices is also the primary output of the MATLAB convhull and convhulln routines.

len(np.unique(hull.simplices.flatten()))

22

The 40 simplices are spanned by 22 points, which means that the other 78 points of our random set are in the interior of the convex hull.

Finally, a welcome surprise to analysing the ConvHull datastructure was to find an equations attribute!

for attr in ['simplices', 'equations', '_points']:

print(attr, ': ', hull.__dict__[attr].shape)

simplices : (40, 3)

equations : (40, 4)

_points : (100, 3)

This $40 \times 4$ array is a horizonal concatenation of the $A$ matrix and $b$ vector in the inequality constraints convention $Ax + b \geq 0$. We will be using the $Ax \leq b$ convention however… This discovery means we actually already have found our vert2con implementation!

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(8, 8))

ax = plt.axes(projection='3d')

ax.add_collection3d(Poly3DCollection(hull.points[hull.simplices], edgecolors=['k'], facecolors=['C0'], alpha=0.9))

ax.set(xlim=(-2,2), ylim=(-2,2), zlim=(-2,2))

[(-2.0, 2.0), (-2.0, 2.0), (-2.0, 2.0)]

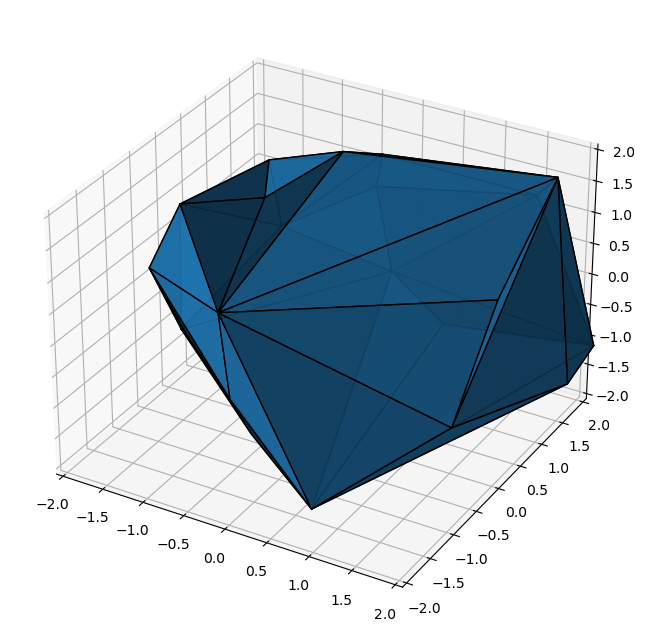

Plotting convex hulls with shading

If we try to enable the shade flag of the Poly3DCollection function, we don’t get any nice shading unfortunately:

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(8, 8))

ax = plt.axes(projection='3d')

ax.add_collection3d(Poly3DCollection(hull.points[hull.simplices], edgecolors=['k'], facecolors=['C0'], alpha=0.9, shade=True))

ax.set(xlim=(-2,2), ylim=(-2,2), zlim=(-2,2))

[(-2.0, 2.0), (-2.0, 2.0), (-2.0, 2.0)]

The reason is that, unfortunately, the simplices that the ConvexHull routine returns are not ordered consistently such that the normals point outward… And we so write a function that fixes these normals: We take any internal point, e.g. by averaging all points of the points attribute, and check whether the normal (cross product of oriented edges) has the same ‘sign’ as the vector from the internal point to any point of that particular simplex. If not, then we reverse the order of the 3 corners.

def fix_normals(hull):

xyz_ip = np.mean(hull.points, axis=0)

simplices_fixed = []

for i, s in enumerate(hull.simplices):

p0 = hull.points[s[0]]

p1 = hull.points[s[1]]

p2 = hull.points[s[2]]

n = np.cross(p1 - p0, p2 - p0)

v = p0 - xyz_ip

#print(i, s, np.sign(np.dot(n, v)), A[i, :] @ xyz_ip <= b[i] )

if np.sign(np.dot(n, v)) > 0:

simplices_fixed.append(s)

else:

simplices_fixed.append(s[::-1])

return simplices_fixed

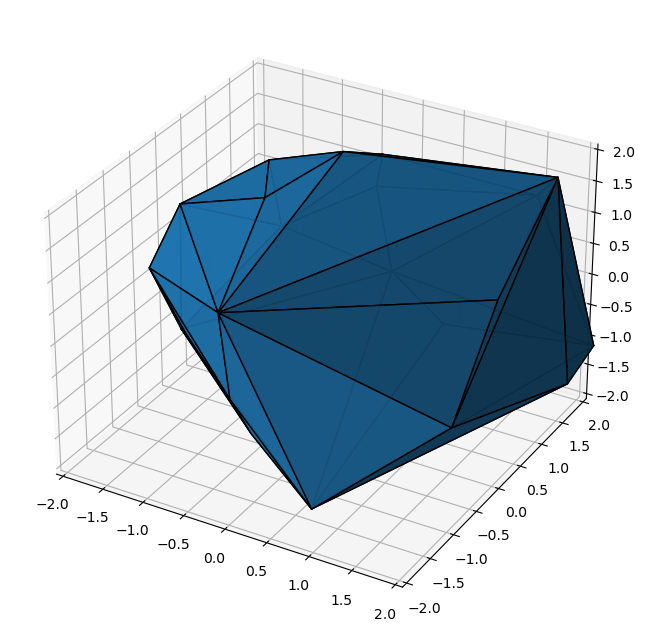

def plot_hull_v1(ax, hull):

simplices_fixed = fix_normals(hull)

ax.add_collection3d(Poly3DCollection(hull.points[simplices_fixed], edgecolors=['k'], facecolors=['C0'], shade=True, alpha=0.9))

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(8, 8))

ax = plt.axes(projection='3d')

plot_hull_v1(ax, hull)

ax.set(xlim=(-2,2), ylim=(-2,2), zlim=(-2,2))

vert2con: a Q-hull approach

As the MATLAB convex hull routines only output the simplices, but not the inequalities, the MATLAB vert2con function that can be found on the MATLAB File Exchange requires an additional 10-20 lines of code to convert the simplices into constraints. In Python we are lucky as the SciPy’s convex hull function already returns inequalities by default:

def vert2con(vert):

""" Convention A @ x <= b """

hull = scipy.spatial.ConvexHull(vert)

A = hull.equations[:, :-1]

b = - hull.equations[:, -1]

return A, b

con2vert: A ChatGPT-based translation

For our purpose of visualizing linear constraints, vert2con is actually not strictly needed, but con2vert definitely is: We need to be able to get vertices for the plotting routines from our inequality constraints $Ax \leq b$. On the MATLAB File Exchange, one can find a con2vert implementation by Michael Kleder, who also authored the related vert2con. The functions used in the project were actually more recent and general variants called vert2lcon and lcon2vert which also can deal with linear equality constraints, e.g. when your vertices all lie in a lower dimensional subspace.

I could not quickly find a Python code that does something like con2vert and I thought it would be a nice exercise for ChatGPT (we are 2023…). The lcon2vert code is significantly longer and more complex than con2vert, and we don’t need that equality constraint feature for now, so I translated con2vert, which is like 25 lines of MATLAB code, using ChatGPT.

My prompt was: The MATLAB code below calculates the vertices of a polyhedron represented by inequality constraints A*x <= b. Please translate to Python code using only Numpy as a dependency

A = randn(20, 3);

b = ones(20, 3);

c = A\b;

if ~all(A*c < b);

[c,f,ef] = fminsearch(@obj,c,'params',{A,b});

if ef ~= 1

error('Unable to locate a point within the interior of a feasible region.')

end

end

b = b - A*c;

D = A ./ repmat(b,[1 size(A,2)]);

[k,v2] = convhulln([D;zeros(1,size(D,2))]);

[k,v1] = convhulln(D);

if v2 > v1

error('Non-bounding constraints detected. (Consider box constraints on variables.)')

end

nr = unique(k(:));

G = zeros(size(k,1),size(D,2));

for ix = 1:size(k,1)

F = D(k(ix,:),:);

G(ix,:)=F\ones(size(F,1),1);

end

V = G + repmat(c',[size(G,1),1]);

[null,I]=unique(num2str(V,6),'rows');

V=V(I,:);

return

function d = obj(c,params)

A=params{1};

b=params{2};

d = A*c-b;

k=(d>=-1e-15);

d(k)=d(k)+1;

d = max([0;d]);

ChatGPT replied with the following code: import numpy as np from scipy.optimize import fmin

def obj(c, params):

A, b = params

d = A @ c - b

k = (d >= -1e-15)

d[k] = d[k] + 1

d = np.maximum(0, d)

return np.max(d)

A = np.random.randn(20, 3)

b = np.ones((20, 3))

c = np.linalg.lstsq(A, b, rcond=None)[0]

if not np.all(A @ c < b):

c = fmin(obj, c, args=([A, b]))

if not np.all(A @ c < b):

raise ValueError('Unable to locate a point within the interior of a feasible region.')

b = b - A @ c

D = A / np.tile(b, (1, A.shape[1]))

k, v2 = ConvexHull(np.vstack([D, np.zeros(D.shape[1])]))

k, v1 = ConvexHull(D)

if v2 > v1:

raise ValueError('Non-bounding constraints detected. (Consider box constraints on variables.)')

nr = np.unique(k.flatten())

G = np.zeros((k.shape[0], D.shape[1]))

for ix in range(k.shape[0]):

F = D[k[ix, :], :]

G[ix, :] = np.linalg.lstsq(F, np.ones(F.shape[0]), rcond=None)[0]

V = G + np.tile(c, (G.shape[0], 1))

_, I = np.unique(V, axis=0, return_index=True)

V = V[I, :]

def ConvexHull(points):

from scipy.spatial import ConvexHull

hull = ConvexHull(points)

return hull.simplices, hull.volume

# Example usage:

# vertices = calculate_polyhedron_vertices(A, b)

# print(vertices)

Very impressive! It did not completely work out of the box. Two fixes I had to make were:

- Something with repmat and tiling and how MATLAB matrices and NumPy’s arrays are fundamentally a bit different. MATLAB can not have arrays of shape

(10,)for example… - The algorithm has a step which eliminates duplicate inequality constraints. The inequality constraints are represented by floats and comparing floats is tricky… The MATLAB implementation was doing a

num2strcall with 6 digits or so. That operation got lost in translation. So I inserted something similar back in, but I usednp.round(..., 6)

from scipy.optimize import fmin

def con2vert(A, b):

def obj(c, params):

A, b = params

d = A @ c - b

k = (d >= -1e-15)

d[k] = d[k] + 1

d = np.maximum(0, d)

return np.max(d)

c = np.linalg.lstsq(A, b, rcond=None)[0]

if not np.all(A @ c < b):

c = fmin(obj, c, args=([A, b]))

if not np.all(A @ c < b):

raise ValueError('Unable to locate a point within the interior of a feasible region.')

b = b - A @ c

D = A / b[:, np.newaxis] # A / np.tile(b, (1, A.shape[1]))

hull = scipy.spatial.ConvexHull(np.vstack([D, np.zeros(D.shape[1])]))

k, v2 = hull.simplices, hull.volume

hull = scipy.spatial.ConvexHull(D)

k, v1 = hull.simplices, hull.volume

if v2 > v1:

raise ValueError('Non-bounding constraints detected. (Consider box constraints on variables.)')

nr = np.unique(k.flatten())

G = np.zeros((k.shape[0], D.shape[1]))

for ix in range(k.shape[0]):

F = D[k[ix, :], :]

G[ix, :] = np.linalg.lstsq(F, np.ones(F.shape[0]), rcond=None)[0]

V = G + np.tile(c, (G.shape[0], 1))

_, I = np.unique(V.round(6), axis=0, return_index=True)

V = V[I, :]

return V

At this moment, I actually don’t even really understand how the algorithm works. Like vert2con it uses a convex hull, but now not of the vertices but of the (normalized) linear inequality constraints. But who needs understanding when you’ve got ChatGPT!

vert2con and con2vert are approximately inverse operations, and we can use that to do some quick sanity checks on output sizes. They are not exact inverses in the sense that vert2con will ignore internal vertices by the hull operation and will return inequalities without any redundant constraints. con2vert will ignore redundant constraints and will also not return any ‘internal’ vertices. This means that vert2con(con2vert(A, b)) can actually be used for constraint pruning. Constraints pruning is something I have had on the backlog for my blog for a long time now. I have some code that does it by solving a linear program for each constraint (+ a few tricks). I wonder how this stacks up against this con2vert2con approach?! Perhaps stuff for a future blog post…

Let’s do those sanity checks:

xyz.shape

(100, 3)

A, b = vert2con(xyz)

A.shape

(40, 3)

xyz2 = con2vert(A, b)

xyz2.shape

(22, 3)

This matches with our earlier observation that out of the 100 random points, there are 22 extremal ones.

A2, b2 = vert2con(xyz2)

A2.shape

(40, 3)

np.linalg.norm(A - A2)

6.510828877941378

The shapes are consistent, but the matrices are not the same… This is due to the ordering of the constraints and vertices being arbitrary…

np.linalg.norm(A[A[:, 0].argsort()] - A2[A2[:, 0].argsort()])

1.5065165444983475e-13

If we sort both according to the entries in the first column we get a match. Actually this could still have failed as inequality constraints can have different scaling ($x \leq 2 \Leftrightarrow 2x \leq 4$), but vert2con seems to do something consistent…

xyz3 = con2vert(A2, b2)

np.linalg.norm(xyz2[xyz2[:, 0].argsort()] - xyz3[xyz3[:, 0].argsort()])

7.067546271189727e-14

And this checks out too!

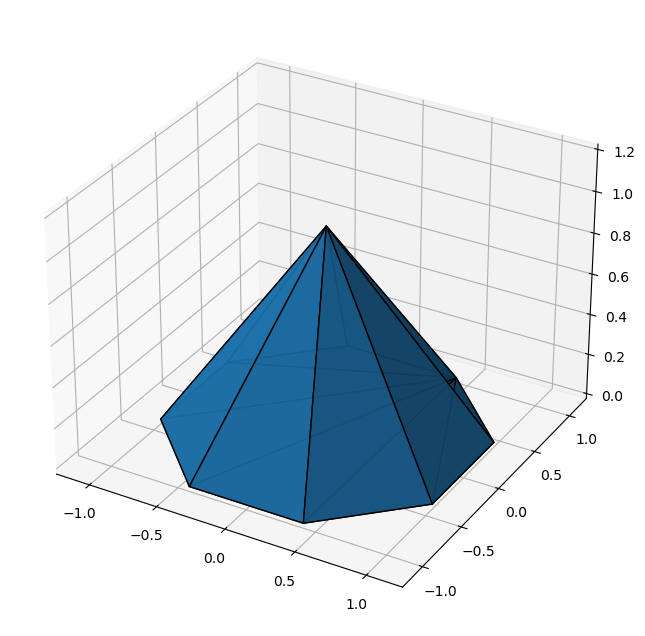

Revisit pyramid case

And with that, it is time to revisit the linear inequality system that we visualized in the preceeding blog post. We defined a pyramid to illustrate how the top vertex is degenerate, and how perturbing the inequalities (e.g. $b$ in $Ax\leq b$) splits that vertex into multiple ones.

We copy paste that ieqs fields that Sage received (with the peculiar convention of ieqs = [b; A]

s = np.sqrt(2)/2

ieqs = np.array([[0,0,0,1], #Ground plane

[1, -1, 0, -1], #1st side

[1, 1, 0, -1],

[1, 0, -1, -1],

[1, 0, 1, -1],

[1, -s, s, -1],

[1, s, s, -1],

[1, s, -s, -1],

[1, -s, -s, -1]]) #8th side

b = ieqs[:, 0]

A = -ieqs[:, 1:]

verts = con2vert(A, b)

print(verts.shape)

hull_perfect_pyramid = scipy.spatial.ConvexHull(verts)

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(8, 8))

ax = plt.axes(projection='3d')

plot_hull_v1(ax, hull_perfect_pyramid)

ax.set(xlim=(-1.2,1.2), ylim=(-1.2,1.2), zlim=(0,1.2))

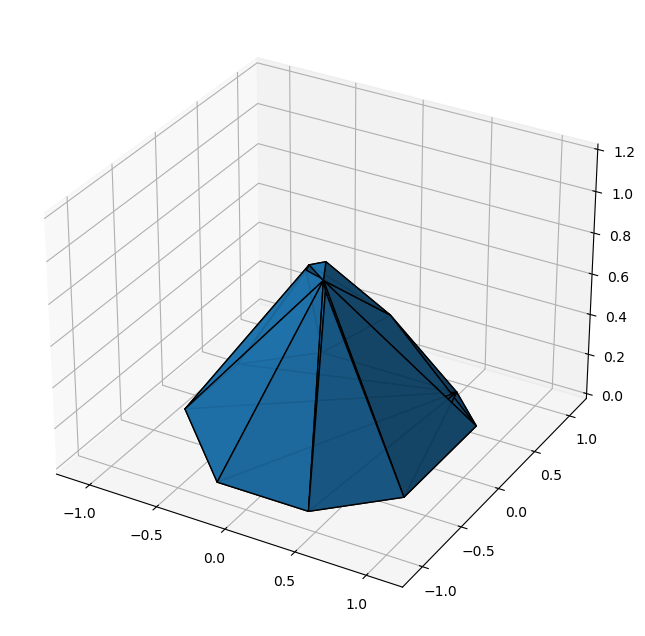

Perturbed pyramid

s = np.sqrt(2)/2

ieqs = np.array([[0,0,0,1],

[0.81,-1,0,-1],

[0.93,1,0,-1],

[0.84,0,-1,-1],

[0.87,0,1,-1],

[0.88,-s,s,-1],

[0.82,s,s,-1],

[0.96,s,-s,-1],

[0.95,-s,-s,-1]])

b = ieqs[:, 0]

A = -ieqs[:, 1:]

verts = con2vert(A, b)

print(verts.shape)

hull_pert_pyramid = scipy.spatial.ConvexHull(verts)

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(8, 8))

ax = plt.axes(projection='3d')

plot_hull_v1(ax, hull_pert_pyramid)

ax.set(xlim=(-1.2,1.2), ylim=(-1.2,1.2), zlim=(0,1.2))

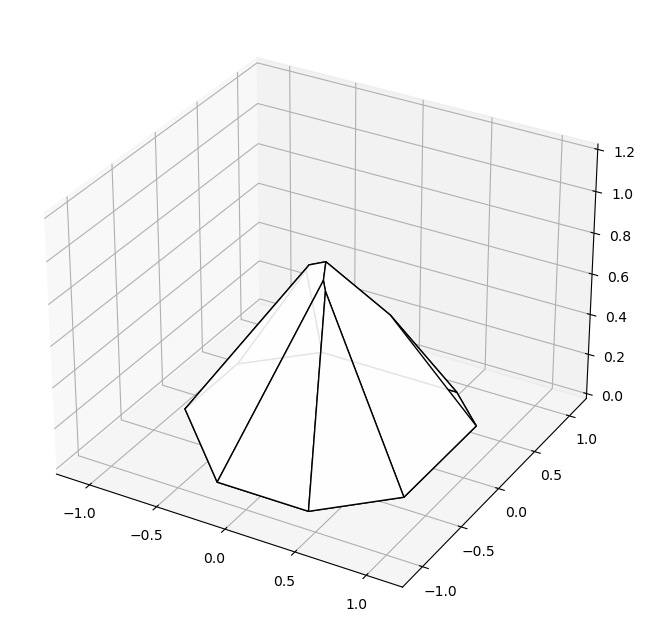

We observe how the perfect octagonal pyramid has 9 vertices, whereas the perturbed one has 14. And one could be content with these visualizations… But I’m not…

The problem with scipy.spatial.ConvexHull is that it returns faces to the polygon as simplices only. So the current plot function cannot have quadrilateral or octoganal faces, even though Poly3DCollection wouldn’t mind… For the perfect pyramid, this means the bottom octagon is triangulated. For the perturbed pyramid it is actually much worse, as the Sage visualization showed much fewer edges than we have now, because many of the side faces are not triangular…

This can be traced back to SciPy calling Qhull by default with the ‘Qt’ option, which divides any face into triangles. So we have two options to go from here: Find a way to call Qhull from Python without the Qt option, or implement a way to merge back the triangles that were split. I went with the second option.

Undo convex hull triangulation

- Step 1 was to check that the

simplicesandequalitiesattributes to the ConvexHull objects have consistent ordering, which checked out. - Step 2 was to group simplices and inequalities that correspond to the same face. I did this on the inequalities, which can be normalized by

- first translating an arbitrary internal point to the origin. This has the consequence that vector $b$ has all positive entries (as now $x=0$ is a point satisfying the constraints strictly, such that $0 = Ax < b$

- next dividing each inequality $i$ by $b_i$ such that $b$ becomes a vector of ones.

- finally performing a

np.uniqueoperation, taking into account that we will want to round to 6-7 digits when comparing floats (very similar to part of thevert2concode actually, and using thenp.uniqueflagreturn_inversewhich contains the info on which collections of entries were equal.

- Step 3 is the merging of grouped simplices/triangles. Also this was a little bit of a puzzle as we don’t know anything about the order of the simplices in the grouping. I settled on an approach that starts with a polygon that is a single triangle at first, and this polygon gets extended with a new vertex for every triangle we encounter that shares an edge with this polygon. It is important to insert the new vertex in the right place in the polygon (which is a list of vertex indices). After every triangle has been processed, we have our merged face. From a complexity point-of-view we are definetely overdoing some work, but one these examples it doesn’t matter.

def merge_triangles(triangles):

polygon = triangles.pop(0)

while len(triangles) > 0:

for triangle in triangles:

joint_verts = set(polygon) & set(triangle)

assert len(joint_verts) < 3

if len(joint_verts) == 2: # joint edge

new = (set(triangle) - joint_verts).pop()

old1 = joint_verts.pop()

old2 = joint_verts.pop()

id1 = polygon.index(old1)

id2 = polygon.index(old2)

id_min, id_max = min(id1, id2), max(id1, id2)

if id_max == id_min + 1: #insert somewhere in the middle

polygon.insert(id_max, new)

else: #new vertex should be placed between last vertex and first one

#Assert id_min == 0, id_max == ...

assert id_min == 0

polygon.insert(id_max+1, new)

triangles.remove(triangle)

break

return polygon

def undo_triangulation(hull):

simplices_fixed = fix_normals(hull)

simplices_fixed = np.array(simplices_fixed)

# Normalize inequalities

xyz_ip = np.mean(hull.points, axis=0)

A = hull.equations[:, :-1]

b = - hull.equations[:, -1]

b_norm = b - A @ xyz_ip

A_norm = A / b_norm[:, np.newaxis]

# Group duplicate inequalities

_, idx, idx_inv = np.unique(A_norm.round(6), axis=0, return_index=True, return_inverse=True)

# Merge triangles into polygons

polygons = []

for i, id in enumerate(idx):

triangles_grouped = simplices_fixed[idx_inv == i, :].tolist() #find all triangles corresponding to an inequality

polygon = merge_triangles(triangles_grouped)

polygons.append(polygon)

return polygons

def plot_hull_v2(ax, hull, undo_triangulation_flag=True, facecolors=None, shade=True):

if not facecolors:

facecolors=['C0']

if not undo_triangulation_flag:

simplices_fixed = fix_normals(hull)

verts = [ np.array([ hull.points[i, :] for i in p]) for p in simplices_fixed]

else:

polygons = undo_triangulation(hull)

verts = [ np.array([ hull.points[i, :] for i in p]) for p in polygons]

ax.add_collection3d(Poly3DCollection(verts, edgecolors=['k'], facecolors=facecolors, shade=shade, alpha=0.9))

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(8, 8))

ax = plt.axes(projection='3d')

plot_hull_v2(ax, hull_perfect_pyramid)

ax.set(xlim=(-1.2,1.2), ylim=(-1.2,1.2), zlim=(0,1.2))

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(8, 8))

ax = plt.axes(projection='3d')

plot_hull_v2(ax, hull_pert_pyramid)

ax.set(xlim=(-1.2,1.2), ylim=(-1.2,1.2), zlim=(0,1.2))

Eureka!

And with white faces it look pretty cool too (and more similar to the original Sage figures)

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(8, 8))

ax = plt.axes(projection='3d')

plot_hull_v2(ax, hull_pert_pyramid, facecolors=['white'], shade=False)

ax.set(xlim=(-1.2,1.2), ylim=(-1.2,1.2), zlim=(0,1.2))

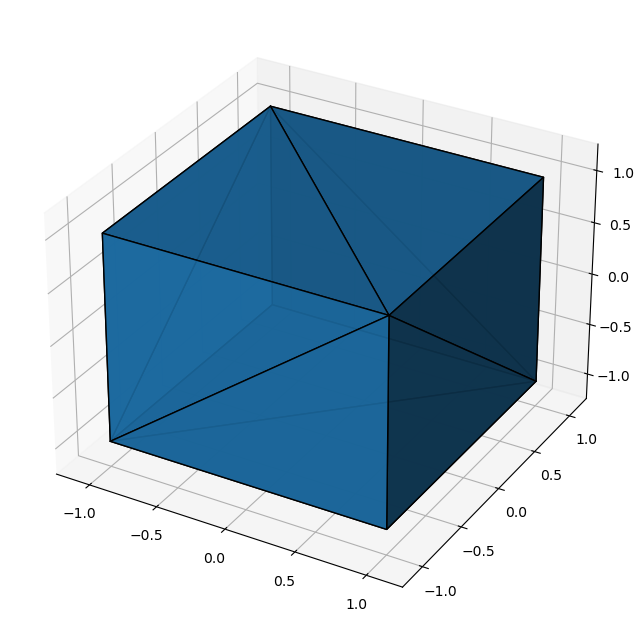

Bonus: Cube test

A = np.vstack((np.eye(3), -np.eye(3)))

b = np.ones(6)

verts = con2vert(A, b)

hull_cube = scipy.spatial.ConvexHull(verts)

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(8, 8))

ax = plt.axes(projection='3d')

plot_hull_v2(ax, hull_cube, undo_triangulation_flag=False)

ax.set(xlim=(-1.2,1.2), ylim=(-1.2,1.2), zlim=(-1.2,1.2))

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(8, 8))

ax = plt.axes(projection='3d')

plot_hull_v2(ax, hull_cube, undo_triangulation_flag=True)

ax.set(xlim=(-1.2,1.2), ylim=(-1.2,1.2), zlim=(-1.2,1.2))

Ending notes

More work than anticipated, but we got there! Near the end of this work, I encountered this Stackoverflow answer that references pycddlib, a Python wrapper to cddlib in which the dd stands for double description (of convex polyhedra). This library can also convert between both formats. However, a quick search gave me the impression that readily available builds are only for Linux and OSX. Moreover, for visualization with Matplotlib, the Stackoverflow post still uses SciPy’s ConvexHull, such that we would still have to deal with fixing the normals and merging the triangles into non-triangular faces…

Related posts

Want to leave a comment?

Very interested in your comments but still figuring out the most suited approach to this. For now, feel free to send me an email.